THE WAR ON

SPORTSWEAR FABRICS

The natural versus nylon debate is heating up, and it’s becoming harder for brands and shoppers to navigate the nuance. Are factories the key to a bipartisan future?

There is a growing contention emerging within sportswear. The activewear market is booming—worth $406.83 billion in 2024 and expected to reach $677.3 billion by 2030—but conversations around materiality are becoming increasingly divisive. On one hand, the unstoppable boom of pilates, which is growing at a CAGR of 14.3%, would suggest demand for spandex-infused synthetics is set to skyrocket; the practice requires form-fitting pieces that enable the body to move fluidly. On the other hand, there is a pendulum swing back towards merino wool, as performance brands look to natural materials that are not only more sustainable, but naturally resistant to bacteria. As customers demand more from their performance wear, sports brands are scrambling to figure out the best solution.

Reddit threads are filled with frustrated women experiencing unhealthy side effects from their synthetic activewear: their leggings are giving them HPV. Second-skin silhouettes made from microplastics mean their intimate areas cannot breathe; it’s a breeding ground for infections. “My [privates] cannot take leggings every day any more!” wrote one exasperated woman on a thread titled, ‘Leggings are consistently bad for down there: what else can I wear?’ The conversation becomes more loaded when layered with global warming. Hotter climates globally create an urgent need for breathable fabric innovations that cater to both personal health and performance. “Natural materials can be more comfortable,” says Laure Baille, head of commercial and wholesale strategy at French activewear label Ernest Leoty.

There is a hierarchy developing where natural materials are loudly being touted as the solution to both. Brands such as Soar, Sums, Literary Sport and Tracksmith have expanded their collections to include more merino wool and cashmere in items such as water-resistant outerwear, socks and shorts. Meanwhile, tennis brands Spence and Horse Sport use only natural materials; The Woolmark Company, the Australian non-profit and global authority on wool, is going hard on its messaging that this natural, biodegradable material is the original performance fabric. It keeps you cool when you’re hot and it keeps you warm when it’s cold; it’s quick-drying, sweat-wicking and naturally odour-resistant. “As a brand, we have been having conversations around materials that derive from oil and the pros and cons of that,” says Rebecca Taylor, head of women’s running at London brand Soar.

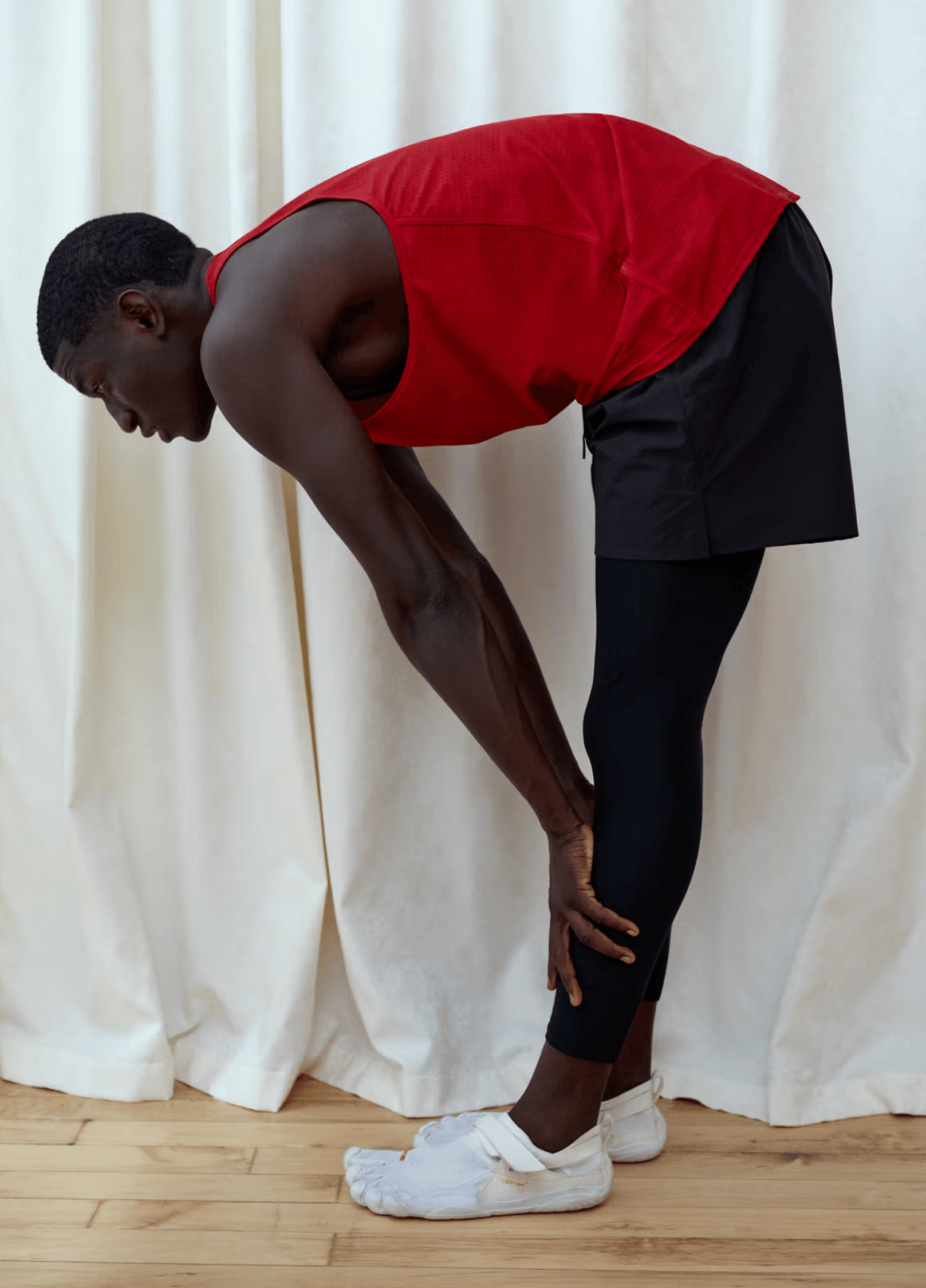

Literary Sport

F/W 24 Lookbook

But natural materials are not entirely superior. The fabric is not abrasion-resistant to withstand the rigour of a trail running pack, for example. Merino is delicate and requires greater care; increased risk of shrinkage can detract from a garment’s longevity; synthetics can seemingly be thrown in the washing machine forevermore. “You have to keep the moths away, it’s also no good for vegans, and it’s an expensive fabric,” says Taylor. “There are also ethical concerns such as how the sheep are treated to consider; brands need to make sure they are buying from a reputable source.”

Not only that, but natural materials do not have the functionality for every type of activity. Leggings and sports bras demand spandex for support as well as fit; cotton leggings that lack stretch bunch up during movement and sag around the knees, ankles and crotch. “Sometimes we need to use synthetic materials because they are just more technical,” says Baille. “For bathing suits, for example, brands need to use synthetics that dry super fast.”

Ernest Leoty is a good example of a brand with an interesting product assortment that speaks to a broader inflection point of activewear. Aesthetically inspired by lingerie, the brand offers pieces designed for the studio but which look whimsical enough to wear as clothing. It caters to customers who are increasingly spending more waking hours working out—offering not just a variety of styling, but a femininity that’s lacking from traditional sportswear. The pieces are designed not just for function, but feel and fashion. “We use a lot of stretch cottons or cotton taffetas to sculpt the body while letting it move freely,” says Baille, of the collection which includes turtleneck shrugs crafted from whisper-thin stretch cottons alongside ribbed knitted bike shorts made from a synthetic blend.

"Sometimes we need to use synthetic materials because they are just more technical"

The introduction of texture into the synthetics market, used prominently by Satisfy (its knife-pleat tops) and Bandit (ribbed and crosshatch spandex) mix the tactility of naturals with the performance of sportswear. This materiality caters to customers who spend more time in their activewear—the fabrics feel dressier than typical shiny nylons and are easier paired with woollen sweaters. There are some beautiful blends available. Soar mixes merinos with silk which makes the fibre have better drape and structure; Tracksmith’s merino tights and shorts are a 57 or 54 percent wool-to-synthetic ratio. Again though, there is environmental and performative nuance here: blended fabrics will not biodegrade like 100% natural fibres will. Equally, not all plant-based nylons are biodegradable or recyclable, and, according to a story reported in the Financial Times in November, the sustainable and alternative fabrics market has collapsed. There is not one easy solution that solves all customer and environmental woes.

Rather than demonising synthetics altogether, brands need to push factories for further innovation. Factories specialising in synthetic development do have the technical infrastructure and know-how to create true solutions. Innovative materials already exist; JoJu’s Italian-made UPF 50+ fabric, which blocks 98 percent of the sun’s rays, will become more in-demand as climate change continues to warm up the planet. Fabric manufacturing as an industry can, and will, transform with direction and demand. Push factories for better-for-you synthetics which have the aeration of cotton and merino wool, but which can withstand the rigour of sport to offer customers true endurance.

"Should customers feel guilty about buying nylon pieces? Should brands focus heavily..."

Ultimately, we think the best products within any market are the ones that are worn. Create the pieces that customers will reach for time and time again; that’s the definition of creating a brand, and garments, with legacy. Materiality is important, but function should always be the priority. Using natural materials that aren’t truly suitable for active purpose, or which sit in a drawer unworn because a customer cannot be bothered to care for it, is not a solution—it’s an environmental disaster. Ease of wear is as much of a problem-solve as clever fabrication.

The noise from customers, brands and the media is louder than ever. But amid all this, we’re left thinking about the factories—those quiet, essential workers behind the scenes who just happen to have the most specialist knowledge in the industry, and therefore, in this conversation. Their voice should be heard, and it should be loud.

Why are these voices currently so quiet? Competition is fierce, and brands are protectionist over their sources and their resources. Gatekeeping the supply chain has become common practice to avoid being trumped off production lines or losing order quantities to bigger brands with bigger budgets. But enabling factories to have more authority is advantageous. With a unique vantage point of the entire industry, innovative factories have the research, development and the know-how to tangibly advance the conversation.

With fabric fluency and interest in origin and traceability increasing, there is a wealth of opportunity for factories here. Will we see more factories turn their technologies into brands in their own right—and engage with customers directly? Goldwin, the outdoorwear brand born from the Tsuzawa Knit Fabric Factory in Japan, is a prime test case, but other fabric technologies like Econyl, Gore Tex, Econyl or Vibram are also a blueprint for materiality as a ‘brand.’ What will be the ‘Sheffield Steel’ or the ‘Northampton Goodyear welted footwear’ of performancewear?

By commercialising an in-house line, factories would in turn benefit smaller labels lacking big budgets for R&D. The more widely available better-for-you fabrics are, the cheaper they become at cost, the quicker the market will adapt. The provenance of an in-house line is a potent marketing story for customers today. If factories built their own B2C relationships, it could empower customers to really choose where they put their money, and, crucially, what they put on their body. Factories could become the decision point, and brands the transaction point. It could reframe the wealth infrastructure of the supply chain entirely, empowering factories and its workers with better pay, more authority and greater influence over both sports culture and the customer pound.

By Grace Cook, Nicola Strange and Ben Gallagher. image credits: Literary Sport, Soar Running, SATISFY, Bandit. Images are used for editorial purposes only; all rights belong to their respective owners.